(they don’t make them like they used to … )

Cratons are anomalously-strong regions of the continents that have largely resisted tectonic forces for billions of years. How such strong zones could be forged in a hot, low-viscosity, low stress, early-Earth has been a long-standing puzzle for geologists. Adam Beall, Katie Cooper and I have recently proposed that cratons were made by the catastrophic switching on of plate tectonics. An event in which the stresses were larger than they have ever been in the intervening 3 billion years (Beall et al, 2018)

Background

The theory of plate tectonics describes how rigid plates move on the Earth’s surface but this really only applies to the oceanic plates. The continental crust is generally a great deal weaker and can crumple or stretch in response to movements of the oceanic plates forming mountain belts, rifts and low-lying basins.

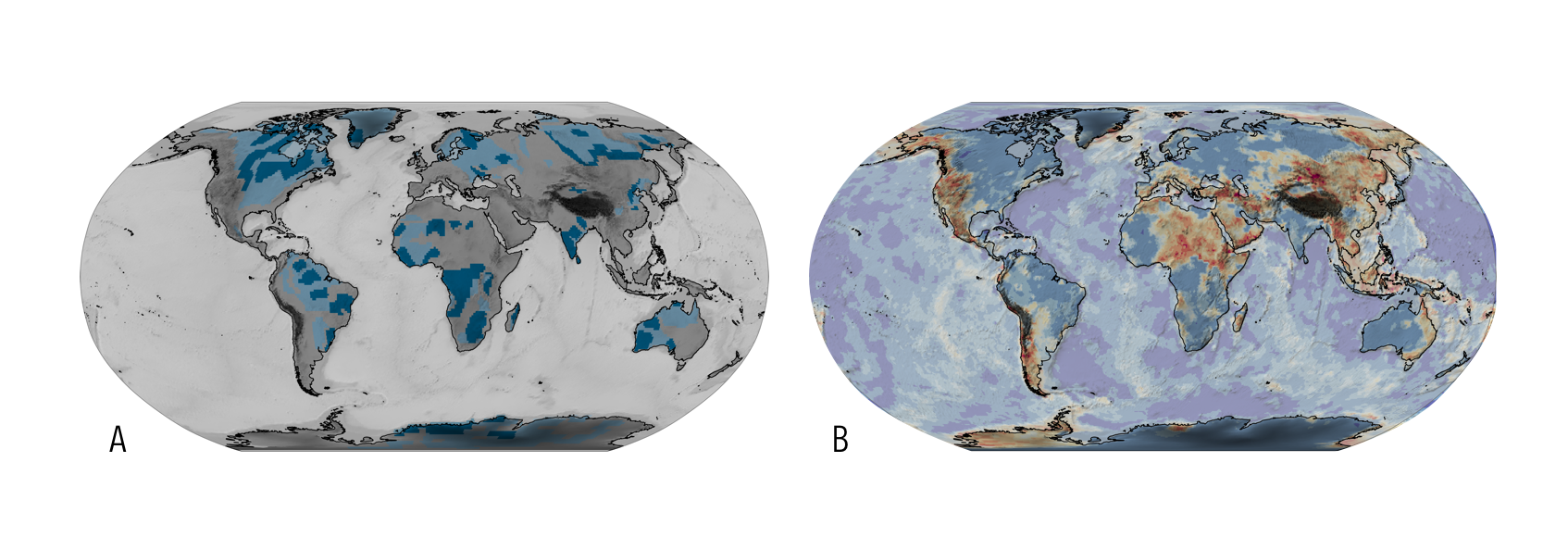

Some of the oldest parts of the continental crust are an exception to this generalisation. These are regions that have experienced very little tectonic deformation in several billion years of existence. These cratons are thought to represent regions of greater strength and this contributes to their longevity. There is evidence that the deep lithosphere is as ancient as the crust and is anomalously thick and buoyant (e.g. Jordan,1975, O’Reilly et al, 2001, Cooper et al, 2013, 2016). We also think that the cratons formed from cool, thin lithosphere in the time before plate tectonics began and then thickened and strengthened to the point where they became effectively indestructible.

The problem with this idea has always been to explain how the hot, weak interior of the young Earth could generate enough stress to thicken strong lithosphere. Alternatively, if the lithosphere was weak too, what stopped it from falling apart by gravitational spreading while it cooled and ‘hardened’ ?

New views

Recent models of the very early Earth showed that the planet could have been cooling rapidly by heat-pipe volcanism (just like Jupiter’s moon Io). Massive volcanism is enough to prevent plate tectonics from switching on, but when the Earth does cool down enough for the eruptions to slow, a catastrophic transition begins. Short, violent pulses of lithospheric foundering and overturn occur before steady plate motions take over (e.g. see Moore & Webb, 2014, Rozel et al. 2017)

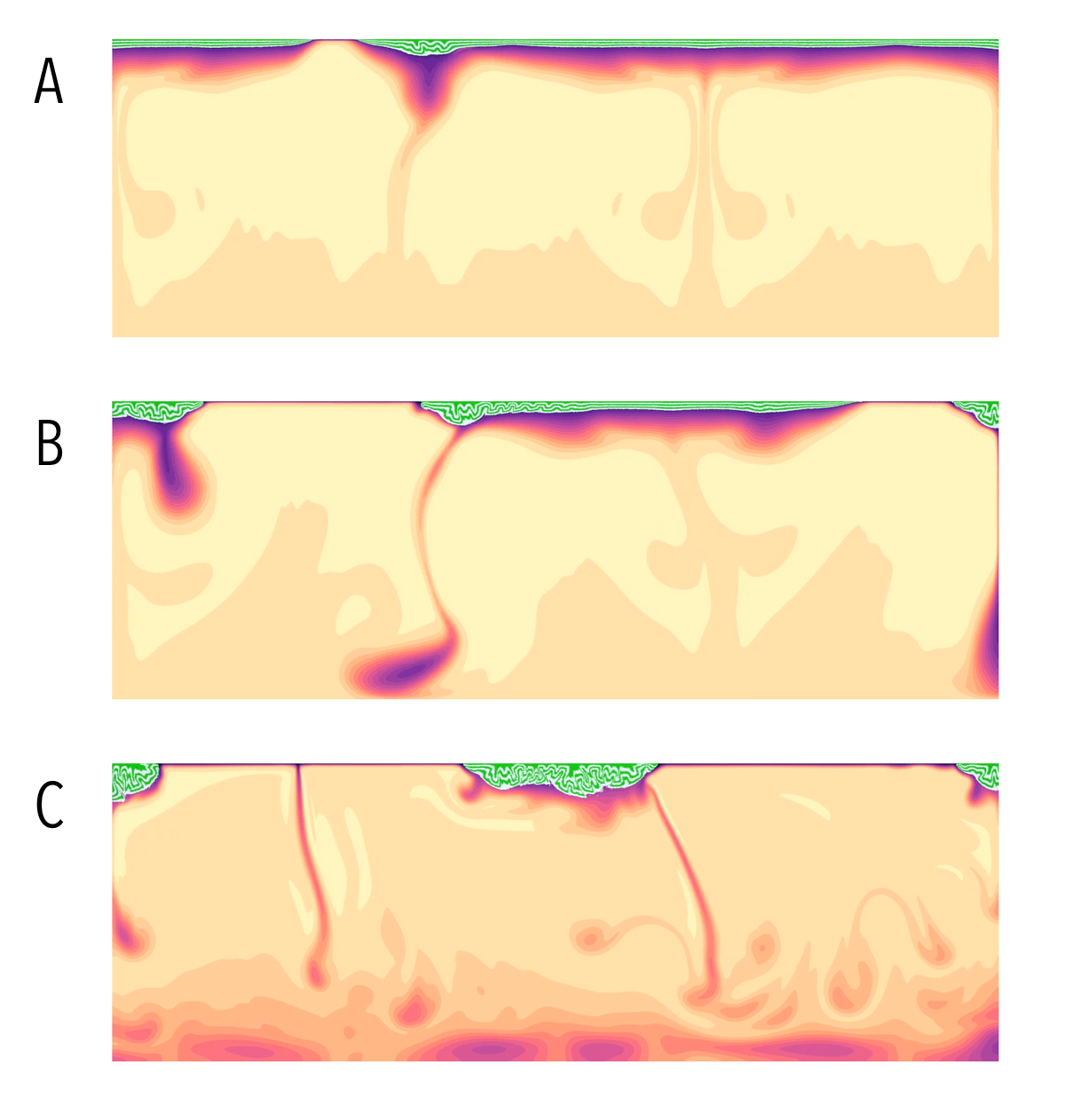

We modeled what happens to the strong and buoyant material of the heat-pipe lid during these early-Earth overturn events. We found that the lid was crumpled up into large islands of thick, buckled and very strong lithosphere by the overturn of the cold, thick, stagnant boundary layer. Once the model Earth settled down to a more sedate form of steadily moving plates, the stresses never reached a level that could deform these remnants of the pre-plate-tectonic state.

In the figure above, the green and grey stripes were initially horizontal layers at the upper surface of the planet and are folded by the foundering of the thick boundary layer. In these simulations, the boundary layer is shed in less than an overturn time. Each model craton experiences a few, closely spaced, shortening events the create a thick pile of material with intricate internal structures not unlike those seen in seismic images that have been attributed to early subduction (Bostock et al, 1998).

The model cratons form cold and from material that was originally crystallised at shallow depth. The formation is also a time of temperature inversion in the mantle: cool material is dumped at the core mantle boundary resulting in higher-than-average core heat flux. The phase of mobile-lid convection that follows this (analogous to plate tectonics in this kind of model) has high velocities near the surface, thin oceanic lithosphere and low stresses. In this environment the cratons are safe from harm and this remains true to the present day despite lithospheric thickness and ambient stresses gradually creeping higher.

Background Reading

The details behind the work described in this post:

- Beall, A., Moresi, L. Cooper, C. M. Formation of cratonic lithosphere during the initiation of plate tectonics, Geology, https://doi.org/10.1130/G39943.1, 2017

Papers on the longevity of the deep cratonic lithosphere:

-

O’Reilly, S. Y., W. L. Griffin, Y. H. P. Djomani, and P. Morgan (2001), Are lithospheres forever? Tracking changes in subcontinental lithospheric mantle through time, GSA Today, 11(4), 4–10.

- Jordan, T. H. (1975), The continental tectosphere, Reviews of Geophysics, 13(3), 1–12, doi:10.1029/RG013i003p00001.

Read about the formation and structure of the ancient continental lithosphere:

-

Cooper, C. M., A. Lenardic, A. Levander, and L. N. Moresi (2013), Creation and Preservation of Cratonic Lithosphere: Seismic Constraints And Geodynamic Models, in Archean Geodynamics and Environments, vol. 164, pp. 75–88, American Geophysical Union, Washington, D. C.

-

Cooper, C. M., M. S. Miller, and L. Moresi (2016), The structural evolution of the deep continental lithosphere, Tectonophysics, 695, 1–89, doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2016.12.004.

Heat pipe models of the early Earth:

-

Moore, W. B., and A. A. G. Webb (2013), Heat-pipe earth, Nature, 501(7468), 501–505, doi:10.1038/nature12473.

-

Rozel, A. B., G. J. Golabek, C. Jain, P. J. Tackley, and T. V. Gerya (2017), Continental crust formation on early Earth controlled by intrusive magmatism, Nature, 545(7654), 332–335, doi:10.1038/nature22042.

The observations of structure in the ancient cratons:

-

Bostock, M.G., 1998, Mantle stratigraphy and evolution of the Slave province: Journal of Geophysical Research. Solid Earth, v. 103, p. 21183–21200, https://doi.org/10.1029/98JB01069.

-

Calò, M., Bodin, T., and Romanowicz, B., 2016, Layered structure in the upper mantle across North America from joint inversion of long and short period seismic data: Earth and Planetary Science Letters, v. 449, p. 164–175, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2016.05.054