Results in computational science ought to be free of the observational uncertainties that make reproducibility so tricky in the experimental sciences. However, even when codes are completely open source, there is not a strong culture of distributing the source code and data files for individual results and this is even more noticeable at review time when, you might imagine, it should be most useful.

Open source is not enough

In Underworld, we have a folder of ‘published results’ as examples for people to see how a particular result was achieved with the code (which is itself open source). The fact that this directory is almost empty is, unfortunately, a testament to how difficult it can be to keep scientific outputs protected from regression when the code is continually evolving. What makes this difficult is also the fact that we are trying to make the results reproducible, we are not supposed to guarantee that you will get exactly the same numbers, only that you will be able to justify the same interpretation of the computation in scientific terms. (This was my original concern about slavish demands for reproducibility. Best not let your science be dependent upon numerical rounding errors or order-dependence in parallel algorithms, and equally, better if your result is not critically dependent on a solver or a fluid-transport scheme). But simple regression testing is not able to make such a subtle detection - the author and reviewers of the paper should really be the ones to make the call.

Software Containers

Another problem which arises in asking people to reproduce your results is it can be a lot of work to install the entire software stack that is needed to make a figure, for example. I discovered just how much work when I tried to release my python map-making class - the installation of the cartopy dependencies is a diabolical torture on most machines !

How can I be sure ensure that my results are truly portable from one machine to another ? If I give you my research in a source-code form, how can I be sure it will actually work for you ? If I am teaching a class, how can I be sure that the examples run identically for every student (and if I ask them to send me their results in a notebook, how can I be sure I am not unfairly critical of a solution that fails to run only for me) ?

Software container systems (e.g. Docker) provide the right level of portability to get around installation problems. They can be configured with all the software dependencies, the appropriate software configuration, and all the information needed to run live examples identically on all machines.

Containers can also deal with the versioning issue - if two versions of the code (or two versions of a dependency) give slightly different results you can keep both and work out if those results indicate a regression of the code, a change for the better, or contingent details that should not influence the scientific results.

Live Documents

If we can control the software environment so well, then we can move towards portable live documents - ones which blend instruction and instructions. Jupyter notebooks are a form of live document – they can execute their own content and provide a way for the reader to explore and evolve the examples provided. They are a natural tool for distributing computational science results.

Not every form of content works well as a jupyter notebook. They have the limitation that all content is live, including any documentation, links and so on. It may not be obvious how to recover if the notebook content becomes corrupted.

And while there are some conventions for approaching unfamiliar content (such as read the README file first), a persistent (immutable !) landing page with navigation links appropriate to the content is probably desirable.

Bundling software into a container

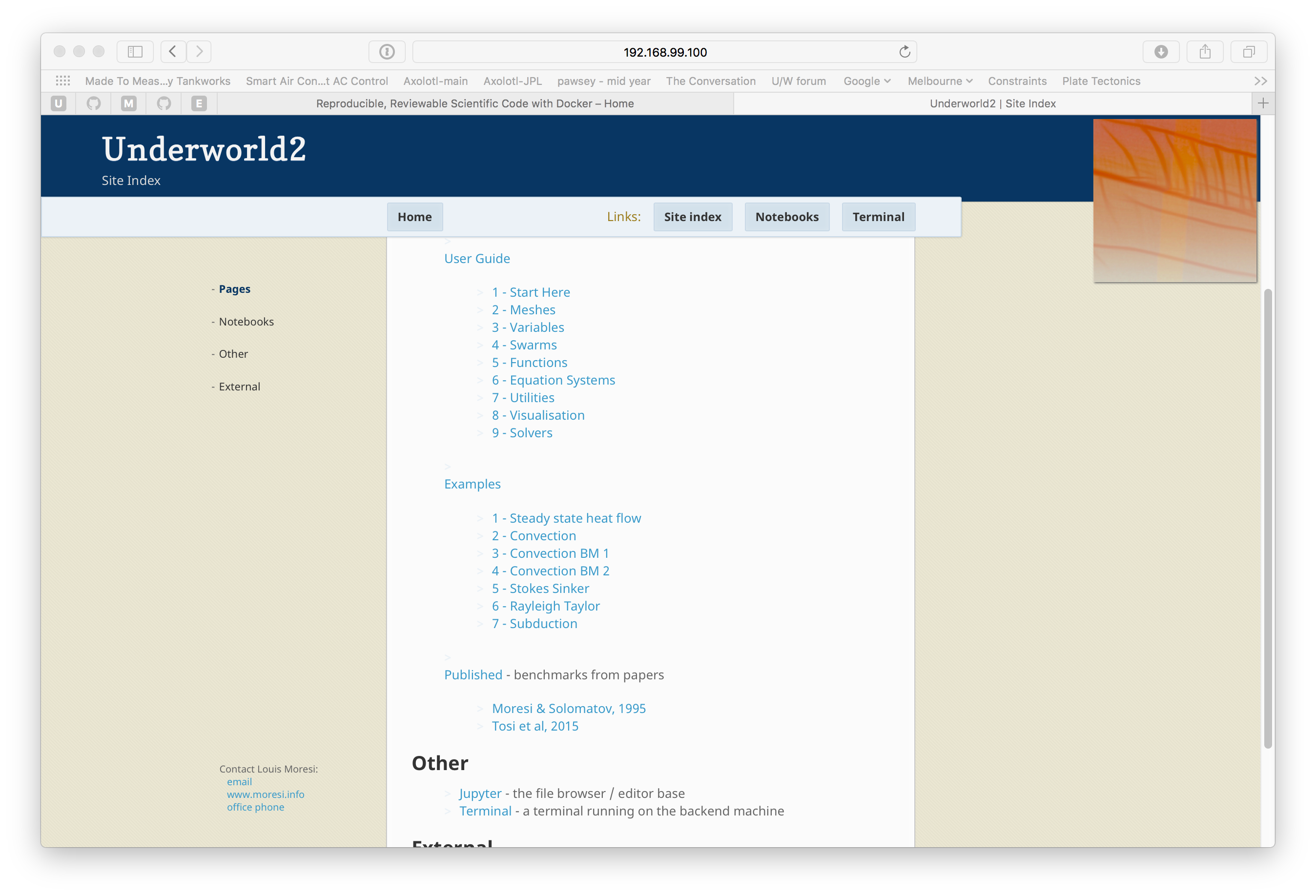

To explore this a little, I have built a module that you can use as a front end for your docker image to bundle together web pages / files / jupyter notebooks. The module contains the jekyll engine to turn markdown files into web pages, example pages / instructions and scripts to set up the jupyter engine to serve the web site and live content correctly.

This module is designed to be dropped into an existing project and built into the front end of the Docker image. It serves web content which is discovered by front ends such as kitematic and dit4c. It relies on the jupyter engine to provide the static web server as well as the capacity to edit files, build and run notebooks, and access the underlying unix layer. The jupyter guys did all the work and I am just orchestrating things to make a consistent front end.

If you want to try it see this docker image which wraps the underworld user guide in a web page and provides a site map leading to all the notebooks we use for documentation. The image is fully loaded with the latest underworld 2 beta …

The source code is available from github and it contains some sample content to show you how to use it.

Read this

Concerning the difficulty of ‘passing’ a benchmark for a scientific result

“Geodynamic benchmarking tests in HPC”; Rebecca Farrington, Louis Moresi, Steve Quenette, Robert Turnbull, Patrick Sunter; APAC’05, the APAC Conference and Exhibition on Advanced Computing, Grid Applications and eResearch 2005. PDF