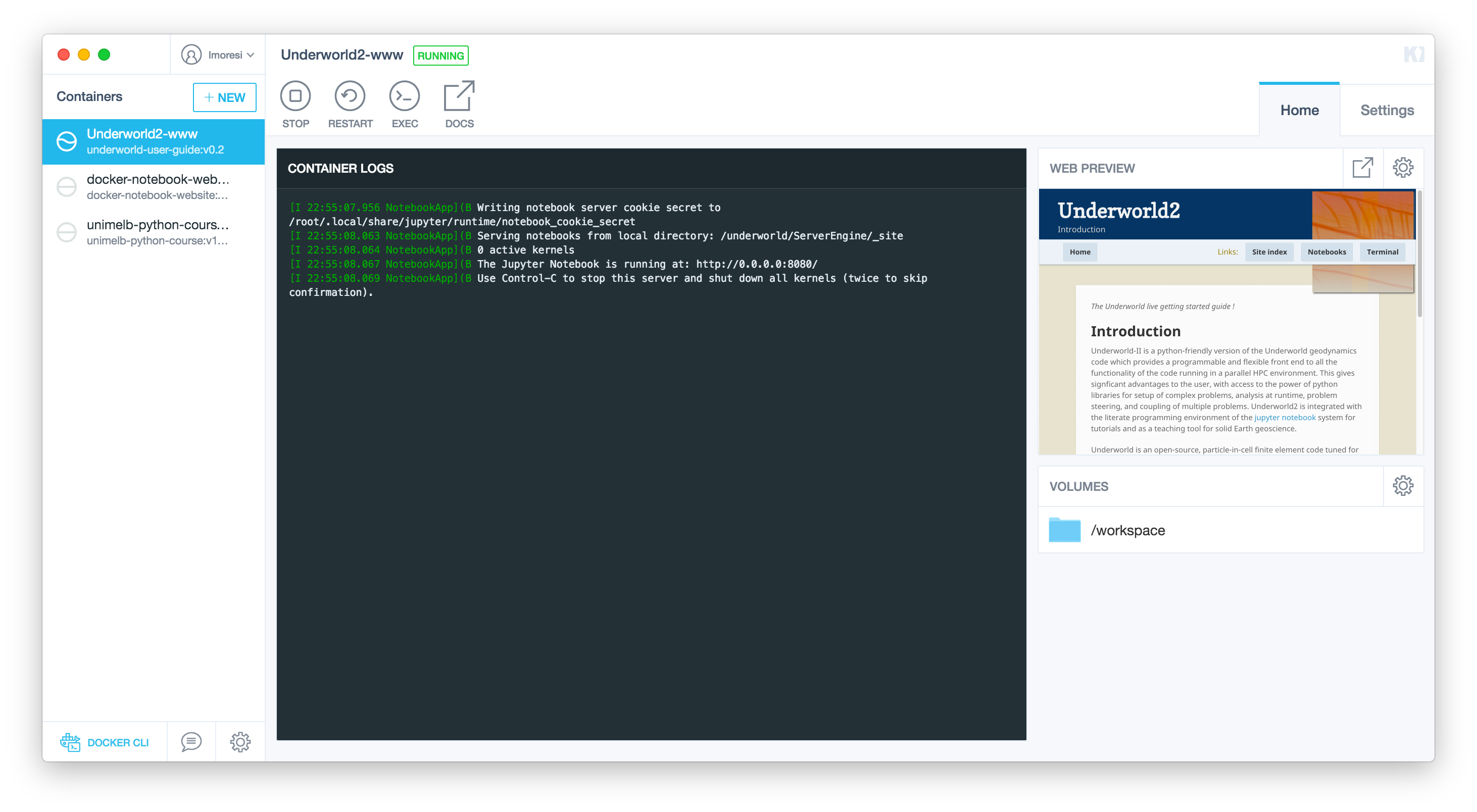

The Underworld team recently decided to focus on distributing Docker images with Underworld2 pre-installed. This was primarily to make our lives easier in deploying our software on multiple platforms. Docker does this by bundling all dependencies from the operating system upwards and any necessary data into a single image which can be run consistently independent of the underlying hardware.

The original motivation of portability also, as an interesting side effect, results in exact reproducibility of results generated by the code.

I have mixed feelings about the need for perfect reproducibility in software results. I remember arguing against the idea when we held the “Data Explosion” meeting in 2006. The idea that perfect reproducibility is the only way to validate a scientific result actually struck me as a dangerous one. Surely no physical phenomenon can be dependent on whether you compiled your code on this or that variant of Unix or which compiler flags were set ? So I thought that recording all of those things was, at best, a waste of effort and, at worst, a complete misunderstanding of what modelling really means.

But, with Docker, the effort argument does not apply and instead we might ask whether it is useful to be able to rerun a computation in a forensic, or perhaps, diagnostic fashion. We might also wonder if it is possible to examine whether the modelling itself was done properly. In order to do this it is not just a question of being able to re-run a calculation but to re-explore the context of the calculation: to examine the sensitivity to the original assumptions and verify the interpretation of the results in developing the conclusions.

In other words, Docker makes is possible to undertake a critical review of a piece of computational science then build upon and extend that work.

This is, of course, what science is all about and is also the philosophy of the open-source software movement. Exactly as we do with open-source code, we need to go to a little more effort to ensure that our docker images are transparent in explaining what the binary layers contain, documenting the installation, that they are clear about the versions of software which are baked in, that we provide documentation of the code itself, include the source, and provide the relevant input files.

Docker really does allow us to bundle up the whole machine, but fully reproducible results / reviewable scientific software demands that we provide not just a black-box, working binary but also transparency at every step along the path to final results.

This is a venerable idea (see Schwab et al, 2000). The guarantee that Docker provides in terms of the run-time environment removes many of the constraints that Schwab et al faced in developing a general procedure for long-lived reproducibility of research results. Nevertheless, a researcher needs to commit to the extra effort required to open-source the whole research process.

References

Schwab, M., N. Karrenbach, and J. Claerbout (2000), Making scientific computations reproducible, Computing In Science and Engineering, 2(6), 61–67, doi:10.1109/5992.881708.

Underworld2 user guide docker container: Docker hub URL; docker pull lmoresi/underworld-user-guide